Avoiding the Corporate Graveyard

If you think hedge fund investors are nothing more than predators feasting on distressed companies or that senior executives shouldn’t be paid big dollars to stay on with firms they led to ruin, Wei Wang has one word for you: Chill.

Turns out hedge funds actually play a productive role in getting bankrupt companies back on their feet. And those “key employee retention contracts”? Keeping senior operating officers involved during restructuring makes sound business sense. If you doubt it, Wei, QSB Assistant Professor of Finance, has research evidence to show you.

“Paying bonuses to executives of failing companies might seem counter-intuitive,” says Wei. “But our research shows it’s an effective strategy for creditors to achieve their objectives.”

In the high-stakes world of finance, these types of against-the-grain insights are big news, and Wei has attracted plenty of attention from the likes of The Wall Street Journal and The Globe and Mail. In fact, 2012 has been a very good year for the young scholar. Besides making the media rounds to discuss his work, Wei, 34, has presented his findings at eight seminars and research conferences, including prestigious forums in Paris, France, and Stanford, California. This is no small feat: the Paris Spring Corporate finance Conference, for example, accepted only 12 papers from more than 300 submissions. A recent paper Wei co-wrote was awarded Best Conference Paper at the European Financial Management Association Annual Meeting in Barcelona in June.

As icing on the cake, in mid-November Wei received QSB’s New Researcher Award in recognition of his scholarly work. In his acceptance speech at a ceremony at Goodes Hall, Wei gave a shout-out to professors Wulin Suo, Lynnette Purda, Lewis Johnson, and Louis Gagnon. These seasoned QSB scholars were at Wei’s side during his PhD studies at Queen’s, and they now count among his colleagues.

On display that afternoon was Wei’s exuberance and sense of style. He was dressed in his trademark bold colours: a cobalt blue shirt and black tie. At a research presentation months before, he sported a canary yellow shirt and matching yellow tie. In his photo on the faculty web page, he’s smiling back wearing a bright pink tie. This is an academic who doesn’t mind standing out in a crowd.

Wei took a winding path to his present career in academia. During his undergraduate studies in civil engineering and urban planning at Northwest University in China, Wei was turned on to business and finance by his uncle, a CEO of a trust company and investment fund. Intrigued, Wei decided to pursue a secondary diploma in finance, studying weekends and evenings. Putting theory into practice, he also started trading stocks.

With an eye on an academic career, he pursued a Master of Arts degree in Economics at University of Liverpool from 1998-99, followed by two years in the PhD program, also in economics, at York University. Perhaps ironically, his studies led to an increased interest in finance rather than his chosen field. When an opportunity arose to complete his PhD specializing in finance at QSB, Wei jumped at the chance. In 2006, after four years at Queen’s, he graduated.

Looking to apply what he had learned, Wei signed on as a “financial engineer” at a risk solution company, where he developed mathematical models of credit risk for banks and other credit institutions. Corporate life, however, was not for him. “Too many meetings and politics,” says Wei. “I prefer spending time on something else, like creating new knowledge.”

In 2007, Wei joined QSB and set out to create knowledge. From his experience in the financial industry, he realized that there was a lack of hard research concerning bankruptcy restructuring, mostly because of the difficulty in gathering information.

It was a challenge Wei, a data hound at heart, was keen to tackle. “I love data,” he says. “I don’t know why, but I love collecting data, especially the kind that no one else can get. To do any study in bankruptcy you have to have a good data set, even though it’s hard to obtain from public sources.”

Wei hung out at bankruptcy courts and the National Archives in the U.S., trolling for hard-copy documents that he and his colleagues then hand-coded to make searchable by key markers. “This way, I obtained a unique data set that allowed me to answer questions that no one else could,” he says.

Wei started plumbing his core dataset for insights, particularly in the area of creditor rights. In the 1990s, the bankruptcy process in the U.S. and Canada was largely controlled by shareholders and management. Over the past 20 years, control has swung to creditors such as hedge fund equity firms. Popular opinion is that hedge funds take control of distressed companies with the intention of quickly dismantling them and maximizing profits. They can do so because there are fewer regulatory limits on their investments compared to those held in mutual funds or pensions.

Using his core dataset as a foundation, Wei and colleagues from UBC’s Sauder School of Business and Columbia University conducted a study that showed hedge funds are actually motivated to strengthen, not destroy, companies. Often, they strategically invest in bankrupt companies in order to become major shareholders once the companies emerge from Chapter 11 (known as “loan-to-own” strategy).

Their study, described in an article published in the Journal of Finance, was based on 474 Chapter 11 filings in the U.S. It revealed just how prevalent hedge firm activity has become in the distressed debt market; hedge firms were involved in close to 90 percent of the sample cases.

These activist investors tend to pick situations in which they can have a big impact on the reorganization process. And they get results. According to Wei’s data, having a hedge fund on board means better debt recovery for other lenders; stronger stock performance at the time of bankruptcy filing; and less leveraged debt one year after emergence from bankruptcy. In short, distressed companies have a better chance of recovering from bankruptcy if hedge funds are in the driver’s seat—clearly a story of “efficiency gains” rather than “value extraction.”

A dramatic Canadian example of the power of hedge funds was front page news in May 2012. The American hedge fund Pershing Square Capital Management, which has a major equity stake in Canadian Pacific Railway, forced the resignation of CP’s CEO and five members of its board of directors.

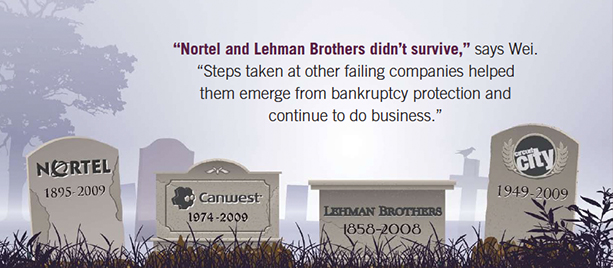

Ironically, sometimes it makes perfect sense to keep existing senior management from leaving companies that are under Chapter 11 protection, as Wei showed in a recent working paper. Management bonus schemes, known as key employee retention plans (KERPs), are often given to leaders of bankrupt companies to entice them to stay through the restructuring process. Many observers see such plans as enriching failed and entrenched managers at the expense of creditors. In 2009, for example, 20 senior Canwest officials shared $8.9 million in KERP bonuses as part of the company’s creditor protection plan, a move that became a flashpoint.

Bad optics aside, KERPs significantly improve the outcomes for creditors, says Wei. Working with Vidhan Goyal of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Wei showed that firms with such plans in place move through restructuring faster and are more likely to be successful after emerging from Chapter 11.

The pair looked at 417 public companies that filed for bankruptcy between 1996 and 2007. Almost 40 percent offered retention plans to key employees. Usually these plans featured bonuses tied to key targets, such as earnings. And, once again, strong creditor control, in the form of activist hedge funds, increased the likelihood that bankrupt firms offered retention plans.

“One thing I found surprising was that the total cost devoted to these plans in the 417 companies studied was less than one percent of the firms’ pre-bankruptcy petition assets,” says Wei. “So why are people so skeptical about these plans? If you think of legal fees, lawyers account for eight to ten percent of assets, but people don’t argue about legal fees.”

He has two more studies in the works relating to the role creditors play in bankruptcy. He’s planning on looking at how costly bankruptcy is for top management and how the loan-to-own strategy affects the governance structure of a company.

Looking ahead, Wei is particularly eager to study the role of lawyers and law firms in bankruptcy restructuring. “These guys play a big role, but there have been no studies,” says Wei. “You know, the poison pill strategy for the deterrence of mergers was developed by lawyers, not corporate finance people. I want to be one of the first to document such things.”

To that end, he spent the past summer painstakingly collecting information on lawyers involved in big bankruptcy proceedings. For a data lover like Wei, that sounds like a summer at the beach.