The Cost of Climate Change Pain

Investing now to reduce greenhouse gas emissions more than pays for itself in reduced physical damages tomorrow

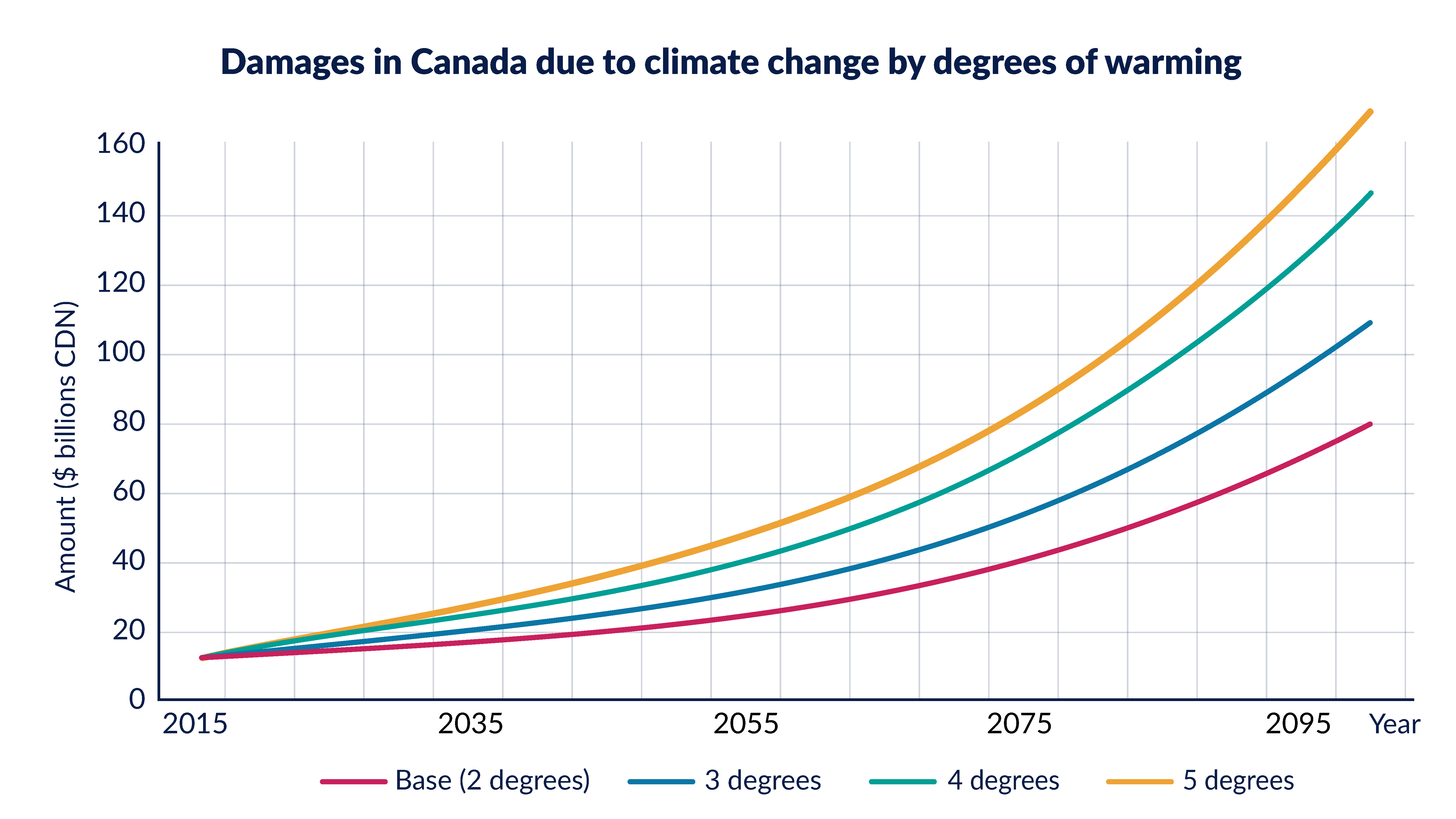

- A new study finds that an increase from two degrees Celsius warming to three degrees by 2100 will lead to an additional CAN$80.9 billion in physical damages in Canada. Under a four-degree warming scenario, damages will escalate to CAN$187.4 billion.

- A significant amount of capital will need to be mobilized before 2030 to avoid the catastrophic acceleration of physical damages related to climate change.

- The required investments cost CAN$10 billion to CAN$45 billion less than climate change damages.

There may be Canadians who secretly believe that freak storms, catastrophic floods and fearsome wildfires are acceptable costs for a future in which snow shovels are quaint museum pieces. Wouldn’t palm trees look good on the shore of Hudson Bay?

You can roll your eyes but how else to explain the lack of urgency in the face of a global environmental crisis? Consider that Canada is among the countries most at risk to climate change. Temperatures in the southern portion of the country are rising at roughly twice the global average rate, and it’s even more severe in the north. Yet, at the same time, Canada is ranked as the worst performer among G7 nations in meeting targets on greenhouse gas emissions that were set in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The trajectory toward a low-carbon economy in Canada must change, and fast. “If we continue to delay the necessary action of mitigating climate change, we’ll realize significant costs to our economy, which underscores the importance of taking action as quickly as possible,” says Neal Willcott, a PhD candidate in finance at Smith School of Business.

Taking action partly requires knowing, in dollar terms, the cost of transitional and physical risks of a warming planet—hard data to inform decisions that financial institutions, investors and policy-makers will have to make in the coming years.

Costing the risks

Willcott is among a growing cadre of finance researchers attempting to cost out these risks. The Bank of Canada and financial institutions are running a sophisticated scenario analysis to estimate the shorter-term transitional risks—stranded assets such as untapped oil, job loss in carbon-intensive industries and others—arising from the move to a low-carbon economy. The hope is that the market can price in the risks before assets are stranded and the economy goes off the rails.

Willcott is focusing on the longer-term physical risks of a warming climate, notably greater frequency and severity of floods and wildfires, infrastructure damage, drought and loss of biodiversity.

Working with Sean Cleary, chair of the Institute for Sustainable Finance (ISF) and professor of finance at Smith School of Business, Willcott plugged Canadian data into a groundbreaking model developed by Nobel laureate William Nordhaus.The model uses a variety of macroeconomic inputs, such as economic and population growth and productivity, to project gross domestic product (GDP) and climate damages over time, based on carbon dioxide emissions.

Willcott and Cleary wanted to see what the national economy would look like if the planet warmed by two, three, four or five degrees Celsius between today and 2100. Using the model, they could calculate the fraction of GDP lost due to physical damages from climate change. They found that an increase from two degrees Celsius warming to three degrees by 2100 would lead to an additional CAN$80.9 billion in physical damages. Under the four-degree warming scenario, damages would escalate to CAN$187.4 billion.

According to the model, the various scenarios that tie physical damage to each degree Celsius of climate change have similar trajectories for the next eight years. After that, the growth in climate change-related damages really takes off.

“Significant capital mobilization efforts will be necessary before 2030 in order to avoid catastrophic acceleration of damages,” says Willcott. “As the relationship is still relatively linear by this point, the years leading up to 2030 are those in which planning and execution are critical.”

Investments pay for themselves

The years 2050 and 2070 are inflection points, when the costs from physical damages compound and accelerate. If there’s no significant progress in Canada to curb global warming, damages will be at their most destructive levels during the period of 2070 to 2100.

What if Canada’s public sector and capital markets were to marshal their forces today and invest in green measures and technologies to mitigate the impact of climate change? Would those offset the projected costs from wild weather events?

To find out, Willcott and Cleary first turned to a recent report by the ISF. The report estimated that it would take an annual investment of $12.8 billion a year for 10 years for Canada to achieve its Paris Agreement target of a 30 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. The researchers extended these figures out to 2100 and compared them to their physical damage projections.

They found that the required investments cost CAN$10 billion to CAN$45 billion less in present value terms than climate change damages.

“In other words, undertaking the required investments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions more than pays for itself in terms of avoided physical damage alone, and without taking into account the potential economic benefits of transitioning to a low-carbon economy,” says Willcott.

Willcott says these estimates are likely conservative since they are based on trends in global temperatures and Canada is warming faster than most of the rest of the world. They also don’t account for the transitional costs, which will be substantial in Canada with its carbon-intensive industries.

On the other hand, there are plenty of long-term benefits from climate mitigation that can improve the picture. As this study shows, however, action must happen now rather than later.

Says Willcott, “Economic value is sacrificed every day that action is not taken to mitigate the economic and ecological risks posed by climate change.”