How CEOs Show Birth Order Behaviour

Firstborns and younger siblings have very different tastes for risk

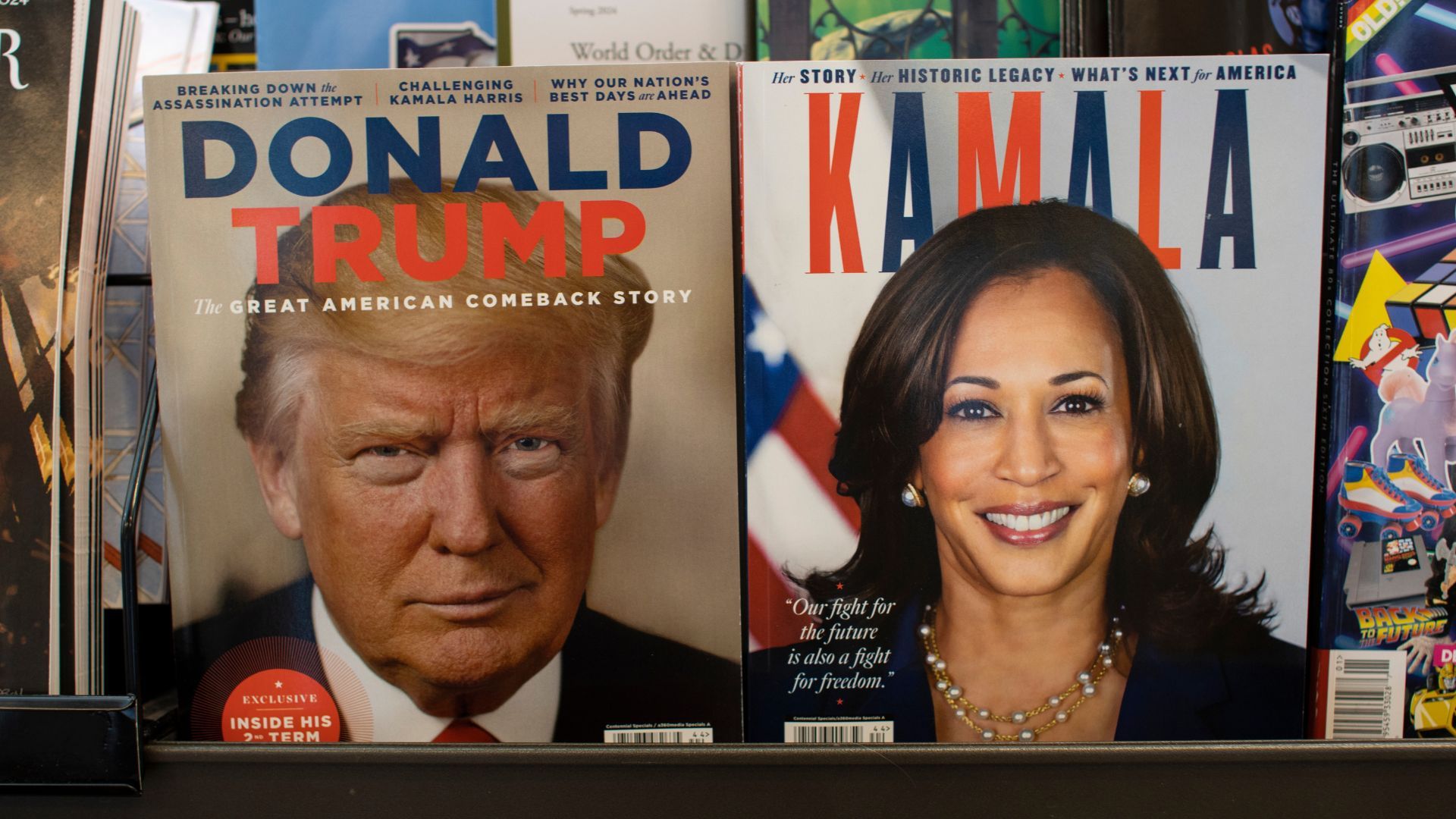

Luckin Coffee’s luck finally ran out early in 2020. The Chinese answer to Starbucks, Luckin was a fast-rising coffee chain until word got out that CEO Jenny Zhiya Qian had fabricated more than US$310 million in sales. In the aftermath, Luckin lost more than 80 per cent of its value before trading in its shares was halted. The spectacular accounting scandal cost the company and Qian dearly— Luckin was delisted and Qian fired.

The scandal caught the attention of MSc alum Yuchen Lin, MSc'20, PhD'25, who is completing his PhD in finance at Smith School of Business. What intrigued Lin was not the scandal or the CEO’s fall from grace but Qian’s place in her family. As it turned out, Qian was the youngest among her siblings, a seemingly arcane fact that actually holds great significance for social scientists who study the impact of CEO birth order on corporate decision-making.

One’s birth order relative to siblings informs early-life experiences within the family. It is a significant determinant of individual behaviour, though how significant is a matter of academic debate. The theory is that parents invest more in earlier-born children, so to preserve their position in the family, older children tend to be more conservative and avoid taking unnecessary risks. Later-born children have no choice but to take risks and be adventurous to differentiate themselves. Such early life experiences tend to have remarkable influence on one’s adult personality.

Organizational researchers have applied birth-order theory to leadership. Their studies have found birth order influences strategic risk-taking, research and development expenses, product innovation and corporate social responsibility. Companies led by a CEO who is the eldest in the family report better performance and have higher credit ratings than those managed by later-born CEOs.

Examining the family tree

Lin looked to add to this body of research. He believed the recklessness of Luckin’s CEO had something to do with her being the youngest sibling; his angle, then, was to explore a potential connection between birth order and risk tolerance by corporate chief executives.

He started by building a dataset based on Chinese firms listed on U.S. stock exchanges. Many CEOs in the sample were the firm’s founders and had been long-time CEOs. Lin painstakingly collected information on the CEOs’ birth order and sibling age gap from Google searches, media coverage and CEO biographies. He ended up with a sample of 78 firms and 96 CEOs. Lin used three markers for executive risk-taking behaviour, all known to have highly uncertain returns: R&D expenditure, capital expenditure and acquisition transactions.

His efforts were rewarded. When he analyzed the data, Lin found “a pronounced positive association” between CEO birth order and the propensity for risk-taking. Later-born CEOs were more inclined to take risks than their first-born siblings, while firstborns were more conservative. Family size, age, CEO political connections, firm size or industry-specific factors made no difference to the results.

He also found that CEOs with longer tenure tended to take on more risks than CEOs who served a shorter tenure, and later-born CEOs with longer tenure were even more aggressive on risky expenditures.

If organizations were to incorporate such findings into their decision-making, Lin says, they could adjust their hiring process accordingly to leverage the phenomenon of later-born managers exerting more aggressive and risk-seeking behaviours.

“Suppose firm owners seek revolutionary change in their firms,” he says. “They would be better off appointing a later-born CEO to implement relatively risky strategies. On the other hand, if an owner is looking for some conservative ‘goalkeeper’, a firstborn CEO is more likely to nail this job.”