Anything But Black

It’s been 20 years since Transformix Engineering launched in the Kingston basement of Peng-Sang Cau, BCom’94. Together with three Queen’s engineering grads, Peng and her fellow co-founders have built the company into a producer of automated machinery that enables customers to assemble small plastic parts or products at high speed. The company has thrived under Peng’s leadership as its CEO.

As a non-engineer at the helm of an engineering company, and as a woman in a male-dominated field, Peng has had to face her share of obstacles. However, none come close to the life-and-death struggle that brought her and her family to Canada from war-torn Cambodia in the late 1970s.

Escape from the killing fields of Cambodia

Peng’s parents had left China for a better life, settling in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, where Peng’s father owned a successful bicycle-parts business. Her mother looked after the family’s ten children and a household of servants, while also serving as the company’s human resources manager. With no schooling past Grade 2, her parents managed to build a comfortable life for the family, until 1975, when the Pol Pot regime came to power. Like nearly all Cambodians, the Caus were displaced from their home and sent to a farm collective, where starvation, torture and death were everyday events. The worst moment came when Peng’s eldest sister was taken away by soldiers, never to be seen by the family again. Terror of a different type followed in early 1979, when the Caus fled gun battles, dodging bullets and the bodies of fallen compatriots when Vietnam invaded Cambodia.

Desperate measures were called for, so the family sold its meagre remaining possessions to fund their escape to Thailand, even though Peng’s mother was heavily pregnant with her eleventh child. During a daring nighttime escape, the family was robbed by a gang tipped off by a paid guide before finally arriving at a Thai refugee camp with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

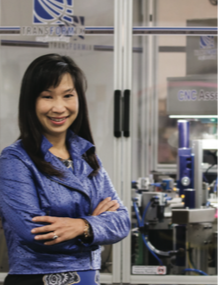

Peng in front of Transformix’s latest innovation, the CNC Assembly TM fabricator. They found safety in Thailand, but not permission to stay permanently. Home was a tent, with raised planks for beds, shared with ten other families. “When it rained, my mother would tell us to go outside and wash up,” Peng recalls. After a year of searching for a country that would offer safe haven, the family secured a new home in Canada with the help of a cousin in Regina.

Peng in front of Transformix’s latest innovation, the CNC Assembly TM fabricator. They found safety in Thailand, but not permission to stay permanently. Home was a tent, with raised planks for beds, shared with ten other families. “When it rained, my mother would tell us to go outside and wash up,” Peng recalls. After a year of searching for a country that would offer safe haven, the family secured a new home in Canada with the help of a cousin in Regina.

Peng remembers the kindness of a fellow refugee couple who gave each child an outfit before the Caus’ departure from Thailand. “They had nothing, and yet they showed us amazing generosity,” Peng says of this couple, who later settled in Montreal and who remain close family friends. She also remembers the long flight from Thailand (she was sick, unused to the foreign food), and her first exposure to TV (“an episode of ‘The Hulk’!”).

A fresh start and new life in Canada

Of course, beginning from scratch in Regina brought new challenges. For starters, not one family member spoke English. Peng’s father initially worked as a dishwasher, budgeting $5/ day for food for the entire family and sending what money he could to relatives and former employees left behind. He also saved enough to repay the Canadian government the cost of the family’s flight to Canada. The entire Cau family remains grateful to the Canadian government for the freedom they have in Canada, Peng says.

All the children had part-time jobs, as newspaper-carriers, office cleaners, and fast-food counter staff. The hard work paid off with the launch in 1991 of Ngoy Hoa Asian Foods, the Cau family grocery store, still operating in Regina under the leadership of Peng’s brothers, Heng and Hee Cau. Another sister, Hung Cau, and brother, Weng Cau, manage the family’s property development company, Syndicau Development Inc.

In this tight-knit family, failure wasn’t an option. “Except for me,” Peng laughs. “I failed Grade 2, but I made up for it when I skipped Grades 3 and 5!” By the time she finished high school, Peng was the top student in her class and the recipient of numerous academic and leadership awards. She applied for university scholarships, despite the fact that, as Peng says, “I’m from a very traditional family with very traditional values, which meant that girls were not allowed to leave home until marriage. My sister, Hung, had already left home to work at Bell Northern Telecom in Ottawa, and my grandma was very upset by this. My mother was not about to allow a second unmarried daughter to leave home and bring shame to the family.”

Peng vividly recalls a summer day after her high school graduation when she was outside, helping bring in laundry from the clothesline. “I mentioned to my mother that I’d received another scholarship offer from Queen’s,” she recalls. “My mother asked, ‘How much?’ and I told her the amount. She waited a moment and then said, ‘OK, leave it to me. I’ll tell Grandma.’”

Peng’s time as a Queen’s Commerce student was her first taste of real independence. It was a difficult experience at first, she recalls. “It felt like a school for the privileged, which I was not. And from Day One, I lagged behind most of my classmates, because we didn’t have Grade 13 in Saskatchewan,” she says. She soon made friends, mostly with engineering students, was involved in the Commerce Society, and went on an exchange to Germany—another life-changing experience, thanks in part to two QSB professors. “On my first attempt, I was turned down because my marks were below the cut-off,” Peng explains. “Later, Prof. Frank Collum told me how disappointed he was that I hadn’t fought for myself, since I was less than a percentage point below that cut-off. I’ve remembered that lesson. Now I question everything and I’m certainly not afraid to speak up for myself!”

The following year, however, her improved marks enabled her to go on exchange. During her term at the Kaiserslautern University of Technology, she went on a trip to various NATO and EU organizations organized by then-professor and former brigadier-general Don Macnamara. “It turned out that he had been part of the Canadian military contingent at the refugee camp in Thailand where my family had lived!” says Peng.

Transformix launches: From humble beginnings to manufacturing success

Following her graduation from the Queen’s Commerce program and a brief stint at Unilever in 1995, Peng joined three Queen’s electrical engineering grads, Martin Smith (’94), Ken Nicholson (’92), and Richard Zakrzewski (’93)—whom Peng later married— to launch Transformix.

The Cau family the day they left a Thai refugee camp for Canada. Peng is in the front, second from right, standing next to a friend. The Cau children’s colourful outfits (gifts from a refugee couple who “had nothing”) were a welcome change from their former black uniforms.The co-founders started small, with a contract to produce 2,500 boxes to encase apartment building alarms. One contract led to another, until the company had found its niche as a producer of automated machinery that enables customers to manufacture small plastic parts or products at high speed. The company has grown to employ nearly 50 workers housed in two facilities totalling 90,000-sq-ft on the outskirts of Kingston. Its newest innovation, CNC Assembly TM—a flexible, high speed assembly technology—will be the subject of an upcoming episode of ‘How It’s Made’ on the Discovery Channel and was the runner up in the 2014 Most Innovative Technology chosen by the U.S. Medical Device Briefs magazine.

The Cau family the day they left a Thai refugee camp for Canada. Peng is in the front, second from right, standing next to a friend. The Cau children’s colourful outfits (gifts from a refugee couple who “had nothing”) were a welcome change from their former black uniforms.The co-founders started small, with a contract to produce 2,500 boxes to encase apartment building alarms. One contract led to another, until the company had found its niche as a producer of automated machinery that enables customers to manufacture small plastic parts or products at high speed. The company has grown to employ nearly 50 workers housed in two facilities totalling 90,000-sq-ft on the outskirts of Kingston. Its newest innovation, CNC Assembly TM—a flexible, high speed assembly technology—will be the subject of an upcoming episode of ‘How It’s Made’ on the Discovery Channel and was the runner up in the 2014 Most Innovative Technology chosen by the U.S. Medical Device Briefs magazine.

The company and its products have also been showcased on the world stage. In 2014, Peng participated in Canada’s trade missions to the Netherlands and China in the spring and fall. Led by Prime Minister Harper, the tours brought together cabinet ministers and Canadian business leaders invited by the government, for the purpose of increasing Canada’s exports abroad. On both trips, Peng was one of only a few women, and the only female CEO of a manufacturing enterprise.

Peng-Sang Cau’s definition of success

Life in Kingston is remarkably calm in comparison to the turmoil of Peng’s early years. This single mother of two divorced and bought out her former husband’s share in Transformix several years ago. Now engaged to be married again, Peng is looking forward to the next chapter of her busy life. In addition to running the business as a very hands-on CEO, Peng is on the board of Kingston General Hospital and is a member of the Research Matters Advisory Panel of the Council of Ontario Universities. She was inducted into Kingston’s Business Hall of Fame in 2010, was named Kingston Business Woman of the Year in 2011 and is the 2015 recipient of Queen’s Jim Bennett Achievement Award “for her entrepreneurial spirit and leadership in Kingston’s business development.”

Peng is a frequent guest speaker, often asked to relate the story of her success in business and in life. “I’m from a humble family; we all worked very hard. I don’t consider myself a big success,” she muses. “I don’t drive a fancy car. I don’t live in a big house. But I do have a great wardrobe!” she laughs. (Ed. Note: she wore a white silk embroidered jacket over a white jersey dress and killer patent-leather stiletto heels with gold studs the day of our interview.) “Maybe that’s because I spent four years during the Pol Pot Regime wearing a government-issued black tunic and pants, day in and day out.” When asked how she’d measure her personal success, she pauses. “I have a great four-poster bed. It’s the most comfortable bed you could imagine. Sometimes, when I lie in that bed at night, that’s when I feel like I’ve made it.”

The days of the wooden planks that constituted her bed in the Thai refugee camp are, mercifully, far behind her.

Do you have a story to share?

Pitch your idea to SPleiter@business.queensu.ca. If it hits the mark, we’ll be in touch to provide direction to help you write your article.