Alumni voices: race and racism

These questions came to the fore over the summer as people reacted to the horrific murder of George Floyd. A number of social media sites sprang up in which students and alumni told of their own painful experiences with racism. Business schools in particular were called out, including Smith.

Smith School of Business is taking a number of steps on this front (read our story in this issue) but it’s important to hear from alumni, too. As such, we invited three Smith graduates to write about their own experiences and give their own recommendations for improvements. What they have to say is important, and we hope you take the time to read their stories on the next several pages.

Reconciliation in the Classroom

Robert Andrews, EMBAA’08, on how schools can (and must) do better for Indigenous students.

First Nation people are a waste of resources.” These words were uttered during my EMBA Americas program. I am well-educated, hold an MBA(s) with Distinction, am a Chartered Professional Accountant, and am a doctoral student in a U15 research university. I was recently appointed as an assistant professor in a business faculty. And I am Blackfoot. I do not appear to be First Nation. What this means is that people share with me their thoughts about race in general, and Indigenous people in particular, unadulterated. They tell me what they really think. Many times, it is painful. My fair complexion has enabled me to move into camps of racial intolerance, undetected. I listen, and the attacks hurt. While the above remark was uttered several years ago, attitudes have not changed significantly today.

This has been my experience my entire life. But my thought was always that in academia, people would be more educated, less prejudiced, and therefore less racist. Time and time again, this has proven not to be the case.

Indigenous students hear other students talk of how First Nation people are impeding economic development, forestalling municipal infrastructure, or blockading railroads to protest the expansion of pipelines—economic equivalents of the Indian problem that motivated misguided government policies. I knew a young Indigenous woman who worked hard to improve her life and pursue her dreams; she studied hard and got excellent grades. She got into a competitive bachelor of commerce program, only to be told by peers that she was in the program because of the faculty’s efforts to accommodate the Indigenous learner, not on her merit. Implicit was that she was not their equal, but inferior. The implication: a waste of resources— someone more deserving should have had her place. She told me this as she held back tears. I could hear the sense of defeat in her voice; I knew it was the second or third time she cried, as she was made to feel unworthy by her peers.

We find racism in universities, and on reflection, it should not be a surprise. The university population, from the students to academics, to the senior administrators, reflects more broadly the attitudes of many Canadians. Each remark at university takes its toll on impressionable young adults, compounding all the challenges that the university presents to first- or second-year students. These short assaults are cumulative. Some studies have reported that as many as 40 per cent of Indigenous students will drop out in their first or second year because of racism. Graduate students have dropped out of programs because of racism. As I stated, I have experienced this many times before—when I heard it as a graduate student, it stung. Still, I had years of experience to become resilient to the endemic racism experienced by First Nation people. But it stung. Our undergraduates, as well as many graduates, do not have this resilience.

What can be done about this?

For the instructor, try to understand the First Nation communities and their history. Learn about the local culture of the Indigenous communities in the area. Each Nation has different customs, traditions, beliefs and celebrations. Be respectful of these practices and traditions. Talk to your students, invite them to talk to you. As with all students, try to find pathways to success. Understand that the myth of meritocracy is based on the premise that all start at the same place. As scholars, challenge these assumptions. Meritocracy is often a veil and justification for the privilege afforded to the dominant culture.

Understand that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action apply to you, the professor. They are not merely university policy and limited to the senior administrators responsible for Indigenous affairs. I have heard professors say, “That doesn’t have anything to do with me in my role.” If you live on land that the First People walked on, hunted on, traded on, governed and worshiped on, the calls to action apply to you.

Try to understand the contemporary challenges that students face; they are many and varied. The challenges are unique and, in many cases, the result of chronic underfunding of education, housing and social programs within the communities, and the effects of a government policy that was, in the words of Justice Murray Sinclair, “cultural genocide.”

The impact that the residential schools had on our community members endures as intergenerational trauma, effects that propagate through generations after those who survived the residential schools. I have heard from our dedicated Indigenous students that some will hitchhike to get from their remote community to university. Others must choose between feeding themselves or feeding their children, and so students will come to your class hungry. Understand this is not history; it is in your classes. The residuals of this effort of government policy to “kill the Indian in the child” still exists.

Try to use examples from local Indigenous culture; it is distinctively part of our Canadian experience. As we celebrate our multiculturalism, let us make space for the cultures of our First Nation people. Not as tokenism, but as a genuine opportunity to improve the quality and life of all students, administrators, faculty, and Canadians. First Nation people have much to offer.

For the academic, approach Indigenous research, not as a vehicle for publications and citations, but to exemplify the highest aims of scholarship, seeking truth to improve the quality of the lives of people. Research must be respectful, inclusive and return a benefit to the Nation. The Indigenous culture and ways of life are intellectual property, and these rights must be preserved and protected. Indigenous people are not data, nor opportunities for grants in furtherance of journal articles.

“Some studies have reported that as many as 40 per cent of Indigenous students will drop out in their first or second year of studies because of racism.”

And the academy must recognize academic service as not just the time spent on internal committees, but in the way in which society is advanced through service to the community. Policies should enable, not encumber. Universities should serve our society in tangible ways.

Lastly, what can students do? You must understand existing preconceptions and stereotypes about Indigenous people and other historically marginalized groups. Ignorance is often the cause of sexism, discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community, ageism, ableism and racism. These beliefs are often inherited from others. Learn about others. Students have led many social movements, on and off campus. Business students should not think themselves removed from social justice, equity, racism and intolerance. You will inherit society from us. You will be called upon to help heal inflicted wounds, whether in the workplace or the environment or your community. Demand that your institution’s leaders lead. Remind them of their obligations to create safe learning spaces. If they don’t, step forward. You can drive the change, as students before you have.

In many traditional practices, gatherings are concluded with a prayer. While the prayers differ, many elements across all Indigenous communities are similar. The prayer gives thanks and asks for blessings for those in attendance, their children, their families, and particularly for those disadvantaged in the communities. The prayer reminds us of our sacred obligations to our youth and our early adults, and to be thankful for the guidance of our elders. The prayer reinforces the dignity of all people, young, old, those in need, and those less fortunate, and reminds us they all have things to offer. It reminds us to pray for those who need help. The prayer offers thanks for all the gifts we have received and reminds us of our obligations to share. I am always struck by the warmth extended to those Indigenous and non-Indigenous, recognizing our common humanity and expressing genuine concern for the wellness of all of us. Shouldn’t academia reflect and encourage these hopes and prayers for a better world?

Robert Andrews is the executive director of the Aboriginal Financial Officers Association of Alberta, and is an assistant professor in Indigenous business with Athabasca University.

Assimilation is Harder for Some

David Kong, BCom’14, and recipient of the Medal in Commerce, recalls his first year in Commerce, and the subtleties of racial division.

This summer, as I read stories of marginalization and discrimination written by current and former students, and shared on the Instagram page @stolenbysmith, my first reaction was that of disbelief. I remembered how fun exchange, Commerce Prom and commencement were, and I recounted being woven deep into the Commerce fabric through clubs like QGM, QBR, QUIC and Examblitz. I needed to research my old messages and writings to remember my feelings from my first year. I had forgotten the hurtful edge of my negative experiences, perhaps because these events occurred 10 years ago, or perhaps unconsciously for self-protection.

Like many students, I interviewed for frosh representative positions on several committees, and was not accepted into any of them. It was hard for me, as it was for other students, to rationalize what part of each failure was attributable to my own inadequacies compared to discrimination.

The reality is that the truth lies somewhere in between.

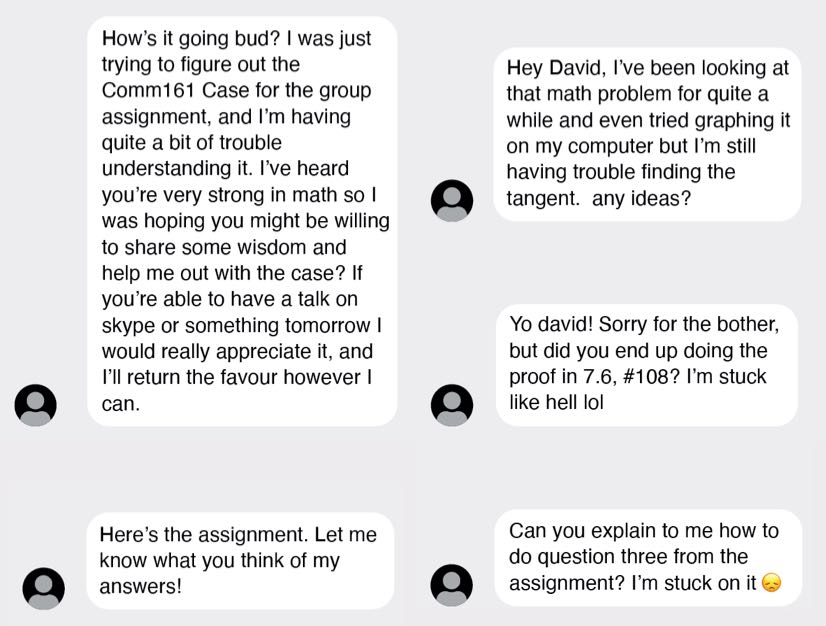

To prove to myself that racial divisions did exist, I re-read all my messages from first year and noticed predominantly white people messaging me (below) to ask for help and predominantly Asian people messaging me to chat.

I looked over an old presentation I made at my birthday party, where I called the first semester the “hardest few months of my life.” In this presentation, I described the school as very “white” and very “rich.” It was a culture shock. I described the “bro” culture and how my vocabulary came to include words such as “kegger” and “iced” in my first year. That is not to say there was no kindness. But it was more likely to come from other Asians. I met my first girlfriend then. She was Korean. I called her the “only good thing in this program” in a chat message.

Racial division is subtle. On the surface, racial undertones are often not substantial enough for students to realize the effects of race. What really happens in Commerce is that students must navigate an environment dominated by exclusive cliques. Anyone, of any race, can potentially be included into these cliques. There were certainly Asian students in many of the desirable cliques. At its core, the program is elitist, and elitism can often lead to worse forms of discrimination.

I remember telling my parents I wish I were not Asian.

My response function was to attempt to break through the racial and cultural barrier. I tried to help others with assignments, going so far as to join groups with predominantly white students. And I took on a campaign of redefining myself.

I ran for election as my year’s socials co-ordinator, putting ads up that read “Beer Kong.” It was a great irony because I abided by the 19-plus alcohol laws and had never had a drink of alcohol prior in my life. A ComSoc co-ordinator at the time is said to have laughed at my campaign, saying it was futile against my more popular opponents. I hosted a Super Bowl party at my house with the help of a white male friend I met—my first such friend in Commerce, an exception to the rule, with whom I am still very close. I latched on to him and he pulled me out of social obscurity. I won the election.

I went so far as to apply to transfer to a different school. My admissions essay read largely like what I wrote above.

To my delight, I was admitted to Brown University in the U.S. But by this time, my strategy to change my image seemed to have worked, and I remained at Queen’s. Helped by my redefined image, I joined QUIC and CREO. And with that came social acceptance. The remaining three years in Commerce were fairly happy. I have cultivated many friendships at Queen’s from diverse backgrounds.

The fact that I was so close to leaving Queen’s shows the situation that many students can find themselves in. We must acknowledge that academic institutions have an exceedingly difficult task of navigating students though the transition to adulthood. A successful matriculating student is forced into contests of academics and popularity reminiscent of the real world. Students are as likely to lose these contests as win them.

“After spending five years in the corporate world, mostly in New York City, I wish I could say things are different in the real world.”

That the program feeds into business, which is largely white and elitist, further presents challenges. To be successful in the business environment, a certain degree of assimilation is required. However, assimilation isn’t easy for everyone. For example, students with accents find it much harder to assimilate. Students from poorer backgrounds or visible minorities will also find it harder to assimilate. This disparity is the crux. Overt racism is limited to the fringes. There are plenty of examples of people of no visible disadvantage doing poorly in this contest as there are plenty of examples of the disadvantaged doing well.

In the Commerce program, there were plenty of Asian people in desirable positions—as class president, a QFAC frosh representative, a QCIB frosh representative, and so on. The elected valedictorian was Asian. This fact pattern echoes much of the dissent against @stolenbysmith. Many Asian people are indeed surprised by the movement because they did well. However, the average is advantage for the privileged.

I have the following suggestions to improve the experiences of Commerce students who find it harder to assimilate:

First, I believe that admissions should be changed. For the most part, alumni should not be used to read Personal Statements of Experience to choose students. The use of alumni engenders like-mindedness, carrying forward and multiplying any biases. Having professors do the reading would be better.

Second, I believe the Commerce program should focus more on academics. That means more engaging and more useful course content, fair methods of evaluation, and allowing students more choice in choosing courses. If academics were more of a focus, then the importance of popularity is lower. Also, professors should not be allowed to reuse exam questions, as this habit rewards students who are more connected.

Finally, ComSoc should (and it seems already intends to) produce reports measuring the success rate of applicants by race, gender, etc.

After spending five years in the corporate world, mostly in New York City, I wish I could say things are different in the real world. But today, when I look through my Facebook messages, ironically, I realize that all of the diversity I have experienced was from my time at Queen’s. In the real world, it is exceedingly difficult to make meaningful connections with people outside of your own race. Most gatherings I attended in New York City were racially homogenous.

What a shame to see in our globalized society.

David Kong left a four-year career at a New York City-based hedge fund to start his own wine-focused businesses, Glasvin and Somm. A longer version of this article was published in the Queen’s Business Review.

You Can’t Be What You Can’t See

Moraa Mochama, MBA’12, on the steps we should take to support Black graduate students.

I was the only Black student. The Only One.

Eight years later, on May 26, 2020, I watched with the world the news of yet another Black man killed by the police. That was on a Tuesday. The day prior, the news had been dominated with the story of Central Park Karen (a white woman in New York City who called police on a Black man birdwatching in the park). By Wednesday, it was the death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet (a Black woman in Toronto who fell off her balcony to her death after the police had been called to her apartment); Thursday and Friday saw the Minneapolis riots and protests in response to the George Floyd murder.

It would be an understatement to say that it was a hard week to be a Black person. It is really hard to try and be your best professional self when images of people who look like you are being brutalized over and over again. By the end of that week, I was mentally and emotionally exhausted. Once again I found myself in a space—at work—where I was The Only One.

When I returned to work on Monday, I pushed my employer to respond to this moment. But I also wanted to see more actions in the worlds I’d been in. I responded to a call on LinkedIn by Matt Reesor, director of the full-time MBA program, to discuss anti-Black racism with past students. As a graduate of Smith, I felt my experience could help future Black students and combat anti-Black racism. Most importantly, I want to ensure no future classes have Only One Black student.

“It is really hard to try and be your best professional self when images of people who look like you are being brutalized over and over again.”

So where do we start? Let me discuss opportunities for change. These are based on my own experiences as a student but can apply to business schools and universities in general.

Coaching

One of the unique selling features of the MBA is the slew of coaching options students have available to them. I’d always been intrigued with the idea of an executive coach, so to have access to one was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. When it came to looking at profiles of the coaches to select for individual coaching, it was disappointing. I was presented with a strong list of truly experienced professionals, but all of them white.

It stood in contrast to our class, which had students from all over the world, representing a variety of racial, ethnic and national backgrounds. It was surprising to see this representation lacking in the coaching staff. A coach is adept at helping you navigate blind spots that could hinder your personal and professional development. These blind spots could be personal traits or professional work; those can be changed with the right level of coaching. But some might be rooted in cultural, racialized or gendered experiences, and a lack of diversity in coaching options leaves students without the tools they need to succeed. Racialized coaches are out there and would be an important addition to the roster of coaches available to students.

On-campus recruitment

On-campus recruitment, or OCR as it’s known, is when recruiters come to the school to meet, interview and ultimately hire from the pool of students. It’s what many in the program spend months preparing for—updating résumés, practising case interviews, researching companies—in hopes of getting noticed, interviewed and hired. Students get a small reprieve from studying to network and meet with professionals.

OCR can be exciting, but I don’t recall seeing a single Black recruiter when I was going through the process. In addition, the representation from other racialized groups seemed to be low as well, and I imagine this was the case at other business schools as well. As a woman of colour, I’m always on the lookout for representation, as it can serve as inspiration because, as they say, “You can’t be what you can’t see.”

Diverse representation in the OCR process can have a significant impact on hiring. In-person networking and hiring is vital for both employer and prospective employee, but it is also fraught. Unconscious biases can creep in when a racially diverse student pool isn’t met with company representatives from all different backgrounds. While schools can’t control who companies send, they can be clear with companies that all kinds of diversity will help them hire better. Companies also have a role to play. When students are immersed in a diverse school experience, they will expect the same level of investment in diversity and inclusion from their employer. Businesses should realize that having a robust diversity and inclusion program is a competitive advantage to their bottom line, and they should look for talent from business schools that cultivates leaders with this mindset.

Student recruitment

When I was looking to get an MBA, I spent time at the Black Business and Professionals Association (BBPA) networking events to learn from other Black professionals and learn about potential career opportunities. But few schools reach out to community and professional organizations that explicitly serve Black people. Organizations like the BBPA, Black Professionals in Tech Network (BPTN) and the National Black MBA Association (NBMBAA), offer connections to Black professionals like me who are looking for growth and advancement opportunities. These are just a few of the many organizations out there that focus on professionals of racialized groups. They can serve as an invaluable pipeline for potential business students.

In addition, I was one of the few students who’d come to the program through work in the public service. Although I’m in the corporate sector now, my background in working directly with the public has enriched my work. Black, racialized and immigrant populations are more likely to be represented within public and community service. The demands of those jobs are immense and the stakes are high. Bringing in students from non-traditional career backgrounds would not only enrich their careers but also the experiences of all MBA students.

Of course, there’s more that can be done. The Reform Smith initiative (a group started by the current students and alumni behind the @stolenbysmith Instagram account) has highlighted other ways, including changes to curricula that can be made. The invitation on LinkedIn from Matt at Smith to discuss students’ experience is a starting point to making change happen. To serve students well during and after they graduate, schools need to keep talking to students about what they need and the challenges they face.

Anti-Black racism doesn’t end just by acknowledging it. It ends when every institution does the work to eradicate it.

Moraa Mochama works as a project manager for a national insurance company. She is passionate about the advancement of women and people of colour in corporate spaces. She lives in Waterloo, Ont. with her husband and two sons