A Missed Connection: Conservative Strategy and the Working-Class Female Vote

Election results reflect a widening gender divide in Canadian electoral politics

Women represent more than 50 per cent of the Canadian population, and there is no easy path to power without their votes.

The Conservative Party’s gender gap in support has grown in each election since 2011, when Stephen Harper closed it, paving the way to a majority government after two back-to-back minorities.

In 2025, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre’s strategy did not achieve the same success in terms of closing the gender gap, as Mark Carney’s Liberals won the election. In fact, his rhetoric and platform both seemed aimed mostly at men, particularly younger and working-class demographics.

Like Donald Trump and other leaders of the populist right, Poilievre’s and the rise on the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) in the polls since 2023 was in part due to strengthening their appeal to working-class voters, particularly men.

Poilievre has spent much of his time as CPC leader courting blue-collar workers and shifting the party’s agenda to include pro-worker policies. The culmination of this was its “More Boots, Less Suits” plan, a package of promises to boost training and apprenticeship grants, improve access to EI, harmonize health and safety policies and provide tax write-offs for trades people’s travel and subsistence costs for out of town work.

These may have been good proposals, but these policies — and the rhetoric in which they were couched during the election campaign — did not seem to offer much opportunity for the party to close the sizeable gender gap in voter intention.

The rhetoric was heavily masculine, including the “More Boots, Less Suits” tagline. The policies in the plan were aimed at workers in sectors that are heavily male-dominated. Women are estimated to represent about five per cent or less of the skilled trades workers that the CPC’s 2025 platform was designed to woo.

How class factors in voting intentions

Drawing on my forthcoming chapter “Gender, Class and Voting Behaviour” in The Working Class and Politics in Canada (UBC Press), we can examine a simple question: Does class affect men and women differently as they decide how to vote?

The CPC has considerable support among working-class voters, particularly non-unionized men, but far less support among working-class women, as my chapter shows based on analyses of the 2019 Canadian Election Study.

This gender difference arises, in part, because there are many more working-class men, according to occupational definitions, than there are working-class women, as noted above in terms of skilled trades.

Poilievre made strong sector- and occupation-based appeals in the 2025 campaign, invoking the idea of blue-collar versus white-collar workers and campaigning on pro-trades policies.

There is a second issue beyond the gender-based occupational segregation in blue-collar jobs. Even among working-class voters, the appeal of the Conservative Party is significantly greater among men compared to women.

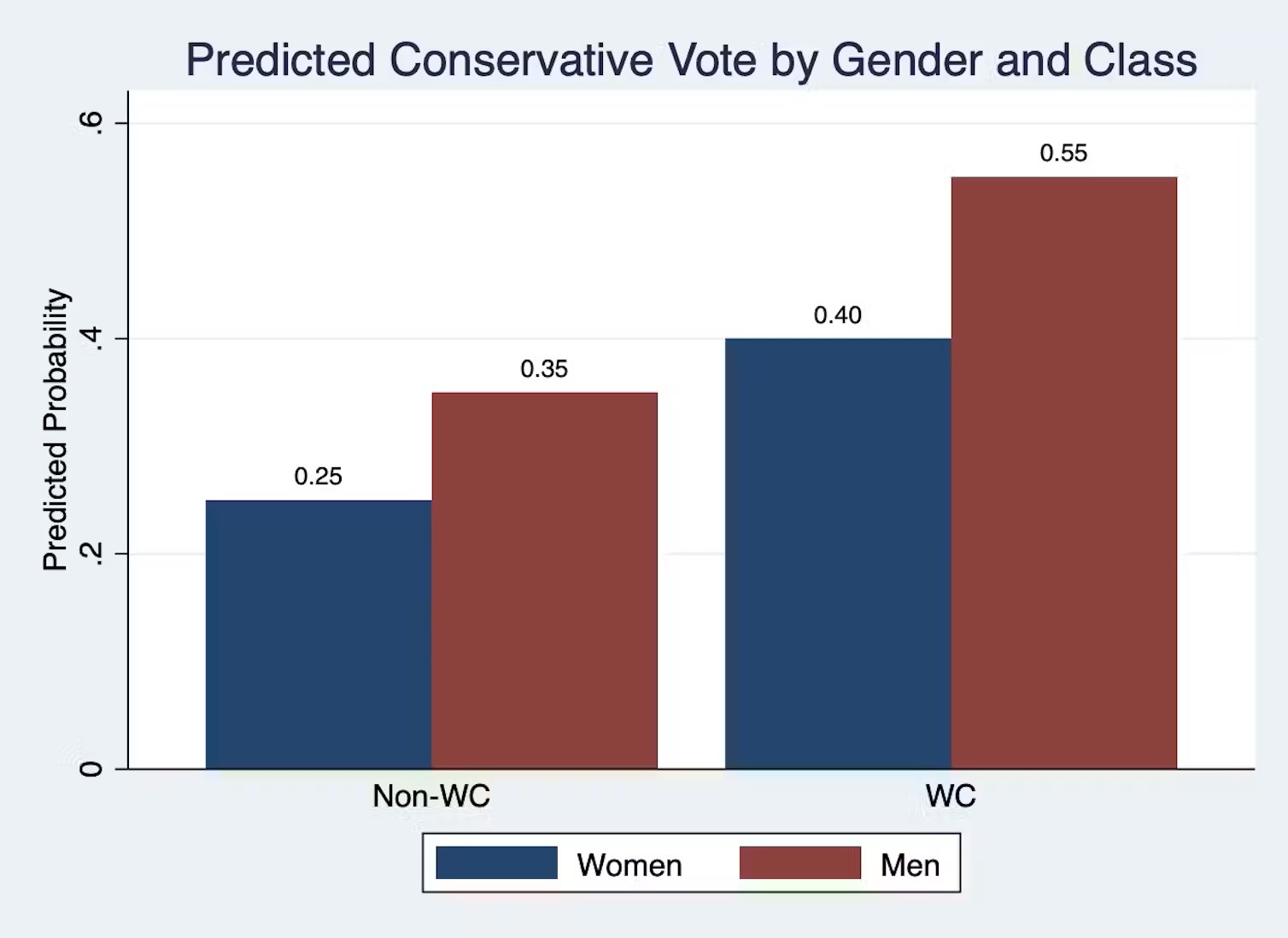

The graph below shows the predicted probabilities of a Conservative vote in 2019 for men and women voters grouped by working-class versus non-working class on a scale of zero to one (with control variables for other factors that influence CPC vote such as income, region and partisanship).

A gender gap is visible in both working-class and non-working class groups, but is largest in the working-class group, with working-class men heavily supporting the Conservatives.

The male-female voting chasm

We can assess these numbers as probabilities that can help us think through how voters cast their ballots in 2025.

Based on the statistical analyses of 37,000 respondents to the Canadian Election Study in 2019, this chart tells us that for working-class men, more than one in two were expected to vote Conservative in 2025, which represents a majority preference.

Predicted Conservative vote by gender and class in 2019. (Original analyses of 2019 Canadian Election Study)

Predicted Conservative vote by gender and class in 2019. (Original analyses of 2019 Canadian Election Study)

In contrast, only one in four non-working-class women would. This makes for a big vote gap — a chasm even — as working-class men form the backbone of the party’s voter base.

Men and women had distinct pathways to supporting Conservatives. But key parts of the Conservative strategy in 2025 limited the party’s potential to appeal to women, even working-class women. “More Boots, Less Suits” offered little to women specifically, or provided them with an opportunity to see themselves reflected in the policy. The broader CPC platform mentioned women only four times.

One mention of women appeared in a promise to end intimate partner violence and consider aggravating factors for violence against vulnerable women. The other three are in single policy promising to repeal a federal regulation on the rights of gender-diverse federal offenders.

There is a widening gender divide in Canadian electoral politics. The Conservative Party’s appeal to working-class men was clear, consistent and electorally meaningful. But this success came at the cost of deepening the party’s gender gap, and this gap is not merely symbolic, but structural.

With women comprising more than half of the electorate, the Conservative Party of Canada’s current trajectory risks locking the party into a limited base. The “More Boots, Less Suits” plan may have mobilized one key demographic, but it did so while alienating another the party could not afford to ignore.

Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant is a professor in political studies and director of the Canadian Opinion Research Archive at Queen's University. This essay was originally posted on The Conversation.